From Camper to Conservationist: Celina Ceballos’ Journey Started at The Wetlands Institute

Celina Ceballos returned to The Wetlands Institute in June to volunteer and help with the terrapins, like this beautiful mother that nested on the institute’s property.

The Wetlands Institute stands proudly in the salt marsh at the foot of the bridge into Stone Harbor. For more than 50 years, it has functioned with a singular mission, “to promote appreciation, understanding and stewardship of wetlands and coastal ecosystems through programs in research, conservation, and education.”

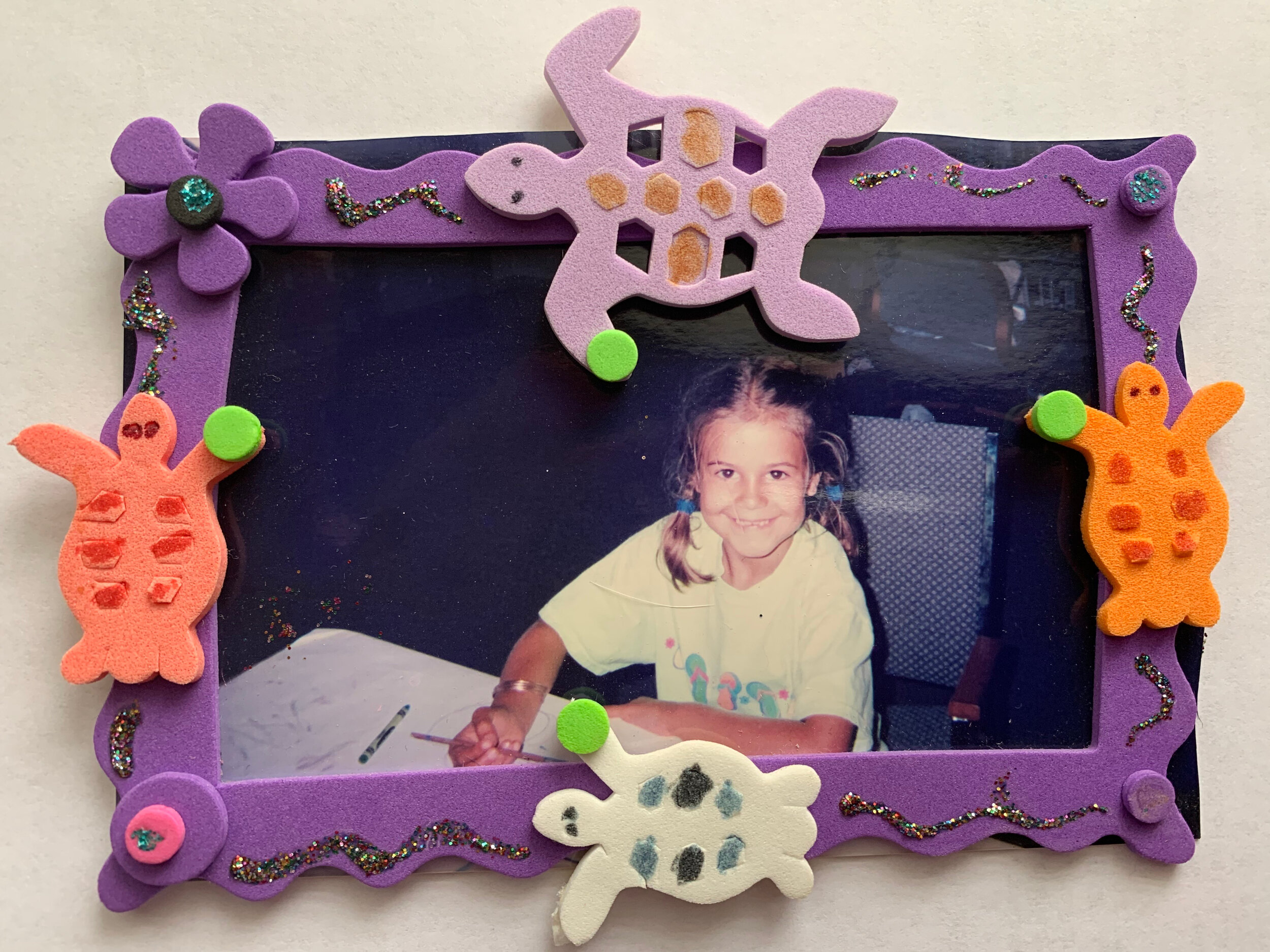

For former Wetlands Institute camper and volunteer Celina Ceballos that mission was more than accomplished.

In fact, The Wetlands Institute lit a spark for Ceballos that led her to a bachelor’s degree in marine science, and a coveted Fulbright Scholarship to study sea turtles in the coral reefs surrounding Honduras.

“I don’t know where I’d be without The Wetlands Institute,” Ceballos says. “As a camper and volunteer, it really helped shape who I am today and inspired my passion for conserving species and protecting turtles.”

It all began months before Ceballos was born, when her parents bought a summer home in Avalon. While she was initially afraid of water, Ceballos soon became the kid who’d never get out of the ocean or pool. To indulge her affinity, her parents signed her up for sailing lessons at the Avalon Yacht Club, and importantly, camps at The Wetlands Institute.

“The Wetlands Institute camp was an awesome experience,” she recalls. “I loved spending time there and learning about all sorts of critters that were in the wetlands. I still remember as a camper walking along the trails and trying to look for turtles and eating pickle grass, which is this kind of edible grass that grows along the marsh. I loved eating it – it just tastes like salt. We would also catch fiddler crabs to feed to the turtles. I always loved being on the water.”

As the years progressed, Ceballos went from student to teacher, first volunteering as a camp counselor, then ultimately finding her true passion in research and conservation. By high school, she was very involved in the Wetlands’ research projects and conservation efforts for diamondback terrapins (the turtles that are prevalent in this area).

Due to her experiences, Ceballos knew exactly what she was looking for in college and beyond.

“I wanted a career in marine science,” she asserts. “A lot of people dabble in it, at least when they’re younger, because they are fascinated by the ocean. But it really went deeper for me. It was something that I was really committed to for a long time.”

She ultimately attended Eckerd College in St. Petersburg, Fla., because of the school’s strong marine science program. After her freshman year, she returned to The Wetlands Institute as a volunteer and got involved in a research project that used radio telemetry to track the movements of turtles in the marsh.

“Radio telemetry and tracking can help in a lot of conservation aspects because we don’t know a whole lot about the turtles on a daily basis,” she says. “Do they stay in one spot? Do they move around? If they’re wandering, why are they wandering?”

She brought that summer experience back to her sophomore year at college.

“I was reminded of the summer project when I was reading literature on gopher tortoises, which are the types of turtles in the nature preserve we studied at Eckerd,” she says. “So, I asked my professor if we could do something like it and he said, ‘Sure!’ So, I started doing radio telemetry with the tortoises in the nature preserve, just like I did at The Wetlands Institute.”

The research would go on to inspire her senior thesis project on foraging and spatial analysis of gopher tortoises.

While graduate school was always part of her planned path to a career in research and academia, a Fulbright Scholarship was a dream come true.

“I first heard of the Fulbright Scholarship when I toured Eckerd and saw a story on a bulletin board about a student who had done research with a Fulbright Scholarship, and I thought that was so cool,” she explains.

The Fulbright Scholarship was established in 1946 and provides grants for individually designed research projects. Fulbright Scholars are expected to meet, work, live with, and learn from the people of their host country in order to foster cultural exchange.

In fitting with the scholarship’s prestigious nature, the application process was rigorous.

“In the summer of 2020, amidst COVID and trying to do research for my thesis, I spent a lot of time on the Fulbright application. It’s pretty tough,” Ceballos says. “You have to be very self-motivated. You have to find your own country, develop your own project proposal, and explain how you’re going to give back to the community.”

Ultimately, Ceballos connected with Loma Linda (Calif.) University professor of biology Stephen Dunbar, Ph.D., who is also the founder and president of ProTECTOR, an organization dedicated to the exploration of sea turtle biology and ecology through research in Honduras.

“We had a couple of Zoom meetings and I talked with him a lot and I decided to focus on the bay islands of Honduras,” Ceballos says. “So, I’ll be in Guanaja, Honduras, studying nesting sea turtles.”

As it turns out, the bay islands of Honduras provide an ideal location to study sea turtles due their untouched coral reefs, which make pristine habitats.

“Studying turtles where they are thriving is ideal, so we know how they behave and what they need in their most natural environment,” Ceballos says. “I chose Honduras because ProTECTOR is such an awesome organization, it’s a beautiful place to study turtles, and since my dad is actually from Cuba, I’ve always felt really tied to Latin America and the various islands there.”

Ceballos is also thrilled for the opportunity to delve even deeper into a subject that is so close to her heart.

“There are seven species of sea turtles and every single one of them are endangered,” she says. “They get thrown so many curveballs, mostly due to human development. For example, plastic bags are a problem because they look like jellyfish and that’s what sea turtles eat. So, a lot of it is plastic ingestion. But the turtles are really important ecologically, on a food web. Some of them are keystone species, so they help preserve the coral reef ecosystem.

“It’s really a shame that we’re having such a detrimental effect on them. But the more you learn, the better you can protect. And it’s important to preserve species like sea turtles, that are so charismatic and really important environmentally.”

As she looks ahead to the adventures that await her in Honduras, Ceballos feels nothing but gratitude for her time in Avalon and at The Wetlands Institute.

“We moved to different places in Delaware and Pennsylvania, but one thing that’s been a constant is coming down to Avalon every summer,” she says. “And The Wetlands Institute is really the foundation of everything that I’ve been working for because I just love it there and I hope to come back to it later in life. I’m really grateful to Dr. [Lenore] Tedesco and Dr. Lisa Ferguson, as well.”

The good feelings are mutual.

“Connecting people to nature and training tomorrow’s environmental stewards is at the heart of the mission of The Wetlands Institute,” says Tedesco, its executive director. “It’s truly inspiring to hear about Celina, and so many other talented young scientists and educators, and to know that our programs helped them find their passion and path.”

Saving and Protecting Diamondback Terrapins

While she was volunteering at The Wetlands Institute, Celina Ceballos became involved in the institute’s Terrapin Conservation Project, established in 1989 for the research and conservation of diamondback terrapins. These are the only species of turtle that live their entire lives in coastal salt marshes, yet due to human development, the species is at risk. Road mortality is a big factor in their decline.

“Mother turtles have to find a spot that’s high and dry,” Ceballos says. “Unfortunately, we have these roads that go right down the middle of the marsh, and that’s their easiest access point to something high and dry. So, the road is there, and they don’t know any better – they’re just looking for a place to nest.”

Ceballos became part of both the road patrol, which assists mother terrapins in safely crossing the road, and the headstarters program, which salvages eggs from terrapins that have been killed on the road.

“When we’d find a mother terrapin who didn’t make it across the road, we could do an eggectomy, where we take the eggs from the mother and put them in incubators at The Wetlands Institute and let them incubate all summer,” she explains.

“They hatch in August, which is super fun to see all the babies. Then we distribute the baby turtles to local schools in the area to take care of for a year. This allows the turtles to get a little bigger and stronger before they are released into the wild, so they have a stronger change of survival. It’s quite a tragedy when we find a dead terrapin on the road, but then we can give the babies another chance at life.”