Cheers to Mayor Bergner: The Brewery Tycoon Whose Legacy Is Still Felt on Seven Mile Beach

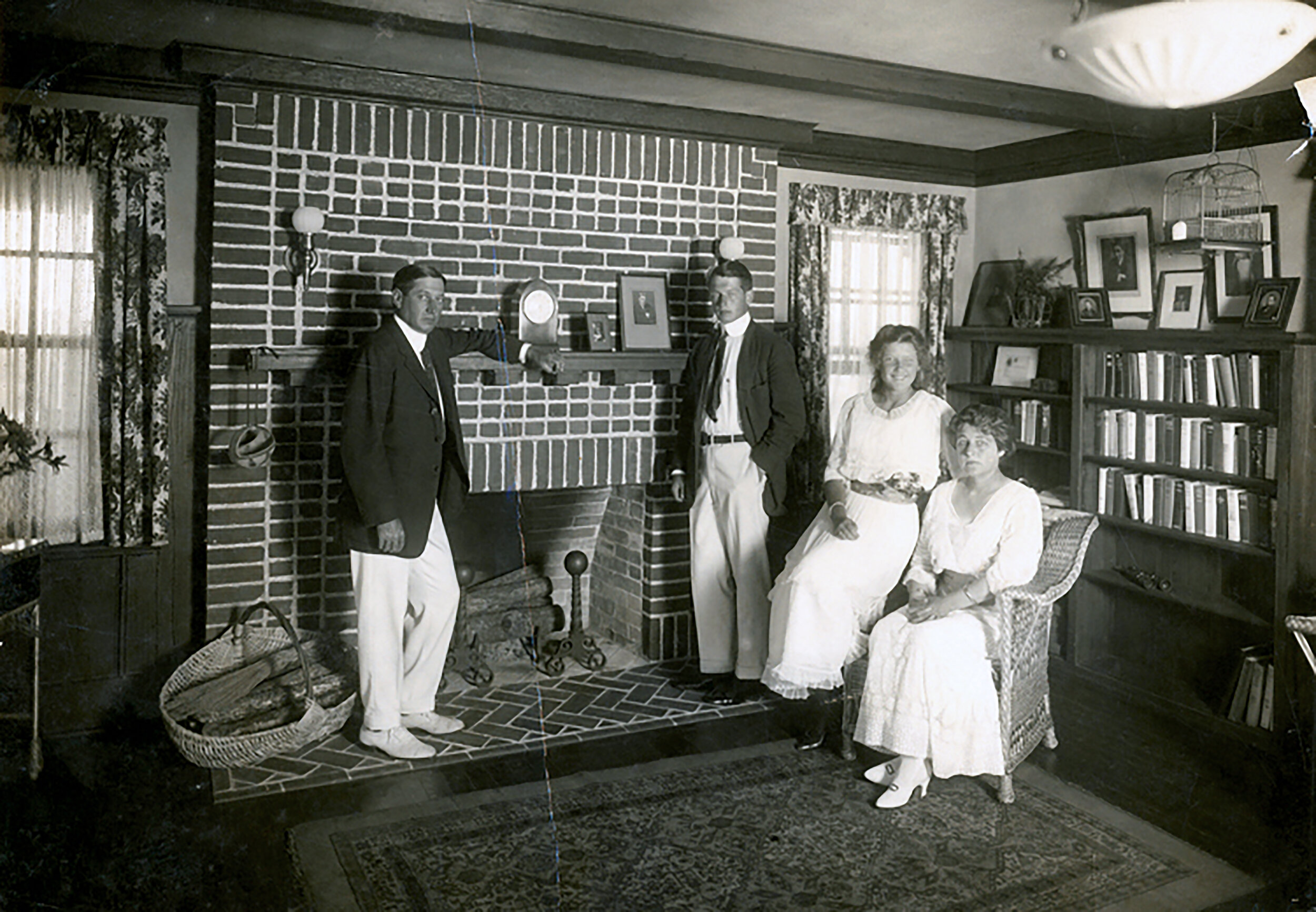

Mayor Bergner’s house, 14th Street & Avalon Avenue.

He was the owner of one of the most prominent breweries in the country and had considerable political clout during the Prohibition era. He was also one of the most impactful mayors in Avalon’s history, credited with bringing important change to Seven Mile Beach during his 12 years in office.

Gustavus W. Bergner headed the mighty Bergner & Engel Brewing Company in Philadelphia before his election as Avalon’s mayor in 1925. His reputation suffered, however, when he was indicted for official misconduct in 1930 and faced a jury trial in 1931.

The popular Bergner, who died while in office in 1937, left behind a legacy that survives today, as he was a driving force behind the Townsends Inlet Bridge between Sea Isle City and Avalon.

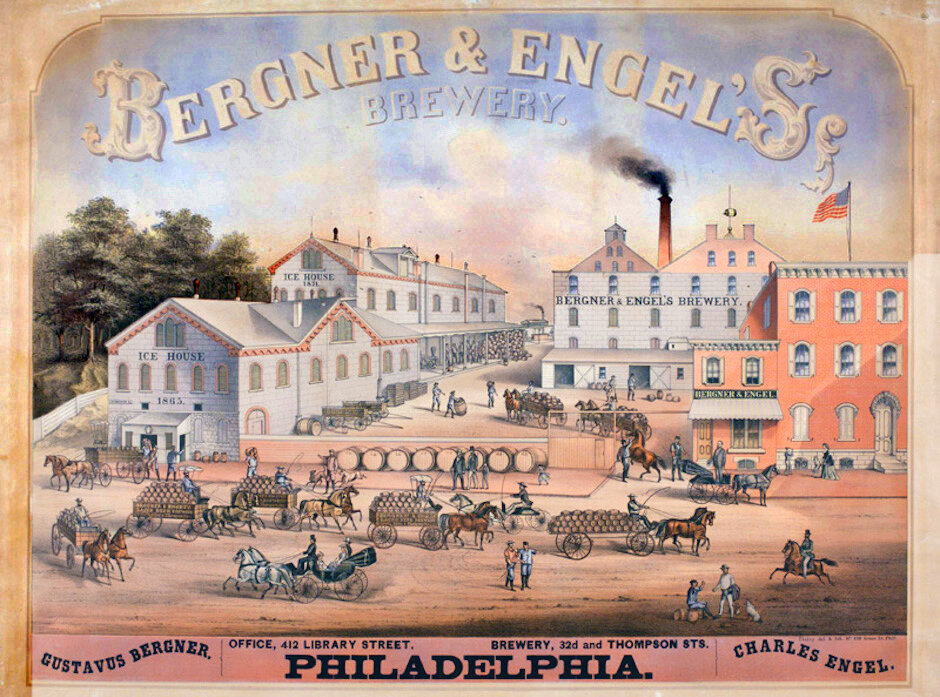

Bergner came from a family of brewers. His grandfather opened a brewery in 1852 on 7th Street in the Northern Liberties section of Philadelphia that was passed down to his father, Charles. In 1870, Charles Bergner built a sprawling brewery at 32nd and Thompson streets in the heart of Brewerytown, a section of the city so named because its nine-block area featured 21 breweries. He also took on a partner, Charles Engel.

Bergner & Engel became one of the most prominent breweries not only in Philadelphia but around the world. Its beers won prizes at the 1878 Paris Exhibition; the Grand Gold Medal in Brussels in 1888, and the grand prize at the 1895 Amsterdam Exposition. The brewery was famous for its Tannhauser Export light beer and Culmbacher dark beer. It was also an industry innovator, one of the first to use refrigerated railroad cars to ship its beer and boasting that it had “the first and only locomotive owned and operated by any brewing establishment in America.”

Upon his father’s death in 1903, Gustavus Bergner took the reins of Bergner & Engel. He became secretary of the Pennsylvania State Brewers Association and also gained considerable political clout thanks to Bergner & Engel’s prominence. When Prohibition became the law of the land in 1920, he fought to save the brewing industry but, in the end, he was unsuccessful as all breweries in the country were closed and padlocked by the federal government.

With his brewery shuttered – as it turned out, for good – Bergner decided to run for mayor in Avalon, where he had a large summer home and four lots on Avalon Avenue. He won a recall election in August 1925. Interestingly, Bergner was swept into office after charges of “negligence and inefficiency” doomed his predecessor, Gilbert Smith, and two other borough Commissioners. Smith had presided as Avalon’s mayor for 27 years.

According to the Cape May County Times, a “wild demonstration” was held by a “great crowd” in front of Borough Hall once the election results were confirmed. Bergner then came out to make a speech on the building’s steps.

“This is a most momentous occasion for me,” he said. “I believe the reason we received such a majority was because the voters favored a more progressive government. We hope to give this to you.”

Soon after taking his oath of office, Bergner went to work to improve the borough. By all accounts, he possessed a dominant personality that helped him achieve many of the projects he proposed, although he was said to rarely be present for commissioners’ meetings.

At the top of his to-do list was to build the Town-sends Inlet Bridge, and he stated at a meeting of the Stone Harbor Council in September 1925 that there were three ways to do it: join with the existing railroad bridge; run parallel with the railroad bridge; or run a bridge across Third Avenue over Townsends Inlet to the meadow in Sea Isle. He believed the cost would be $500,000 to $600,000, with the entire cost of the bridge to be paid by a county tax, and asked for the cooperation and support of Stone Harbor to complete the project.

At a County Board of Freeholders meeting in October 1925, he requested that the Freeholders appropriate funds and labor to hard surface several roads, specifically Avalon Avenue from 13th Street to the railroad. Avalon Avenue was, coincidentally, where the Bergner home stood.

“We know that we have been asleep in this little town for a long time,” he said to the freeholders, “but we are now waking up and going to put Avalon on the map. We are soon going to be a big community and ask that you help us in this matter. I think the county should attend to this road … it is now in deplorable condition. We are also greatly interested in the bridge across Townsends Inlet and will do everything in our power to help it along.”

As the years rolled on, Bergner remained popular with his constituents, and was re-elected several times. His achievements included the establishment of a permanent police force; bringing natural gas to the borough; purchasing a new American LaFrance fire engine; building a jetty at 8th Street and Avalon Avenue, and constructing the Avalon amusement pier and convention hall.

He also became president of the Cape May County Bridge Commission, through which he promoted the construction of connecting bridges between Stone Harbor and Wildwood, and Wildwood to Cape May, as well as a member of the South Jersey Transit Commission, playing a prominent role in the Beesley’s Point Bridge, which connected Cape May and Atlantic counties across the Great Egg Harbor Bay.

But in September 1930, Bergner had a problem. Eleven indictments were handed down by a county grand jury charging Bergner and borough commissioners Wilson McCandless and Charles K. Rommell with illegal expenditures of municipal funds. They were also accused of awarding a road-oiling contract in excess of $1,000 without advertising for bids and paying a commission to the Sea Isle City National Bank for selling municipal bonds below par, a violation of the Pierson Act.

All three pleaded not guilty before Judge Palmer M. May in Cape May Court House on Oct. 8; they maintained that, up to Sept. 1, the borough budget had an unexpended balance of $48,000.

On Jan. 19, 1931, the three men went on trial for the charge of paying the illegal commission to the Sea Isle bank; 10 days later, they were acquitted by a jury that had deliberated four hours.

Despite this episode, Bergner remained in office until May 22, 1937, when he died at Fitzgerald Memorial Hospital in Darby, Pa., at age 63. He did not live to see his pet project, the Townsends Inlet Bridge, completed and opened to traffic in 1939. Bergner is buried in the West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Pa.