The Miraculous Monarch Migrants: Our Annual Visitors Are Coming Through, and They Need Our Help

By Dr. Lenore Tedesco, Executive Director of The Wetlands Institute

It’s fall in Cape May, and that means one thing: It’s time for the great migrations of wildlife headed south to warmer climates and abundant food.

Cape May sits on one of the world’s great migration corridors, and in addition to being on one of these great highways, this narrow peninsula between the Atlantic Ocean and Delaware Bay is also an important stopover point. Think of it as a great truck stop on an interstate system. The abundant beaches, farms, meadows, and forests of the peninsula are perfect places for migratory wildlife to rest and refuel before making the first of many dangerous crossings over open water.

Most people are familiar with the globally famous fall migration of eagles, hawks, and falcons through Cape May, and know that spending time at the Hawkwatch Platform in Cape May Point State Park on a sunny fall day with a good north or northwest wind is a rewarding venture. Perhaps fewer are familiar with the great southbound migration of seabirds that occurs just offshore. The Seawatch on the north end of Avalon is where scientists count the strings of nearly a million seabirds migrating south from their North Atlantic breeding areas. More than 60% of all sea ducks breeding in the Western Atlantic pass by or winter off Seven Mile Beach, making Avalon Seawatch one of the greatest natural spectacles in North America.

Cape May is also an important breeding area for monarchs and a stopover for migratory monarch butterflies as they make their way south to the mountains of Mexico to spend the winter. Butterflies migrate to avoid unfavorable circumstances that can range from weather and food shortages to even overpopulation. The most well-known migration is that of the Eastern population of monarch butterflies, but several other species of butterflies and moths are also migratory. The painted lady, common buckeye, American lady, red admiral, cloudless sulphur, numerous skippers, question mark, and mourning cloak are all butterflies that migrate, and many can be seen in the area nectaring and roosting as they pause on their long journeys.

Monarch butterflies are remarkable and tough. Every time I think of their life history and journey, I marvel at all the things about nature that we just don’t understand. It takes four generations of monarchs to complete a full migration cycle! Monarchs arrive in central Mexico in October and overwinter in the mountains, where they huddle in great masses in a type of pine tree. They sleep in these groupings and rely on mild weather and shared body heat to stay warm. They don’t eat and only occasionally drop to the ground to find moisture. In late February to early March, these monarchs become active, find a mate, and begin the flight northward to lay their eggs – likely making it into southern Texas before they die. These special monarchs have lived about six months through the long winter, and are very different from the other generations that make the monarch migration work. In March/April, the eggs laid by these special monarchs hatch, and this first generation goes through its life cycle – caterpillar, chrysalis, and adult butterfly. These adults fly a little farther north into the Midwest and mid-Atlantic, where they lay eggs and die. This second generation hatches in May/June and goes through its life cycle, flying farther north, where they lay eggs and die. The third generation moves into our area, New England, and upstate New York and Pennsylvania, arriving in July/August. Perhaps you have noticed that we don’t see monarch butterflies until later in the summer. This is why – it’s taken them a flight from Mexico and three generations of offspring to get here! These butterflies lay eggs and it is their offspring – the fourth generation – hatched in September/October that does not die! They live six to eight months and are the ones that will migrate to Mexico and overwinter there to start the journey back north again next spring.

I often ponder this: How is it that a creature so seemingly delicate and fragile can fly that far? How do they transmit the information from generation to generation about their roles? None of them have made the entire flight – each northward-moving generation has only completed a single segment. And they pass the information through four generations to make one complete migration.

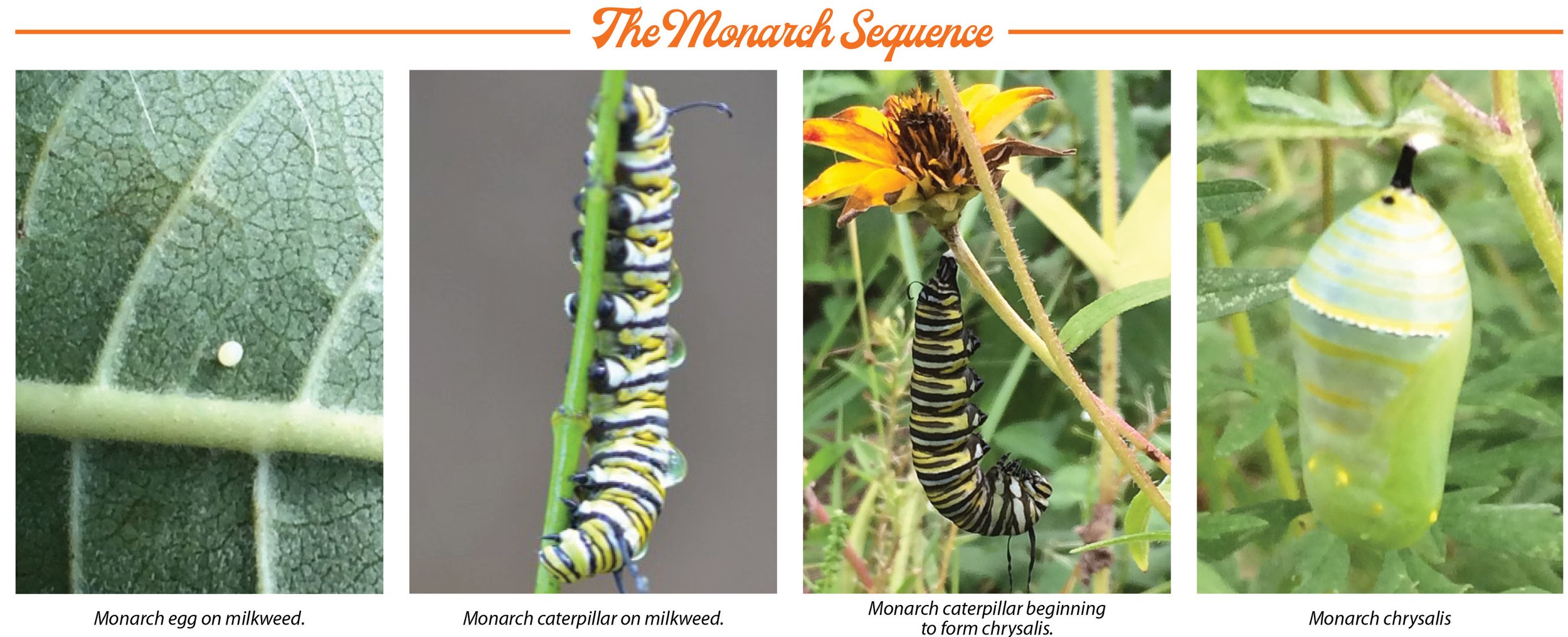

If you consider the life cycle of an individual, it’s even more remarkable. Adult monarchs lay their eggs only on milkweed plants. The egg hatches into a caterpillar with a voracious appetite. The caterpillars eat the milkweed leaves and grow remarkably fast. They are eating machines, and molt at least four times as they grow. In human terms, they eat 40 pounds of salad every day for two weeks. A newborn baby would be the size of a school bus in about two weeks if they ate this much! After this crazy growth, they form a chrysalis, where magic happens. Inside this protective case, the caterpillar turns into a green liquid of protoplasm – a blob of life – that reorganizes itself and hatches out in 10 days into an adult butterfly. And this butterfly has the map and timetable telling it when to leave and where to go. I guess there are just some things we aren’t supposed to understand, and I’m OK with that.

Monarchs are in trouble, though, and need our help. Thankfully, there’s a lot we can do to help ensure that these remarkable travelers can find food for the adults and caterpillars, and that those journeying through south to Mexico have the food resources they need to make a successful journey. Two things are critical: the availability of milkweed for caterpillars, and the availability of flowers in September and October for fuel for the migrants.

The Wetlands Institute has been doing a lot to help these jewels. First, we are planting milkweed everywhere we can. The gardens at the institute are loaded with milkweed. We have also worked with the Boroughs of Stone Harbor and Avalon to create native wildlife gardens at the Stone Harbor Bird Sanctuary and Armacost Park, and there is a wildflower meadow at 118th Street and Dune Drive. All of these gardens have milkweed for monarch caterpillars and an abundance of late-flowering plants, so there is nectar to feed the hungry migrants headed south. Many of these areas are certified Monarch Waystations by Monarch Watch (monarchwatch.org).

Cape May during the fall migration is a special place. The peninsula’s location makes it part of an important flyway, and its rich diversity of habitats and protected environments are key reasons that it has become and remains such an important migratory stopover.

There are challenges. Development and habitat loss continues to be a concern. Invasive and non-native vegetation are also taking a toll, and herbicides and drought have largely wiped out a significant amount of the milkweed throughout the monarch’s range. Perhaps most seriously, climate change is making their journey more dangerous, with ongoing drought in the Southwest, more frequent wildfires, and increases in the number and severity of storms during their flight.

There is still a lot you can do, though. Maintaining native plants in gardens and adding milkweed to your garden is a great way to help. Avoiding herbicides and pesticides is important, too. Making your patch of land welcoming and suitable for these travelers will not only put out the welcome mat so you can enjoy their visits, but also helps give them a helping hand along the way. There are lots of resources to help you plan garden improvements. Monarch Watch has great information. The gardens at the Stone Harbor Bird Sanctuary are a wonderful resource (stoneharborbirdsanctuary.org). The Wetlands Institute has gardens that promote native plants for pollinators, and we have volunteer programs to teach you to be a Monarch Ambassador and help tag monarchs and count migratory monarchs (contact the institute for information). I hope the next time you see a monarch, you will be as amazed as I am.